by Charlotte PLANTIVE

Agence France Presse

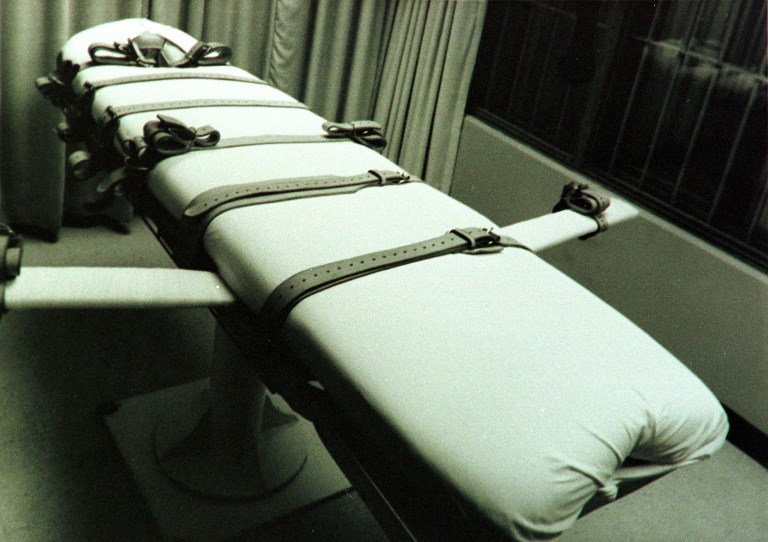

WASHINGTON, United States (AFP) — The Supreme Court is set to consider on Tuesday the fate of a death row prisoner who says the government’s plan to execute him by lethal injection could cause him to choke on his own blood due a rare medical condition.

Missouri death-row inmate Russell Bucklew, 50, was sentenced to death for rape and murder — but says execution via lethal injection would violate the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment because of his condition.

He has backing from more than a dozen former prison wardens and directors, who have written to the top US bench asking that the justices consider their suffering as well.

“When you have a botched execution, the ones who suffer are the ones who have to carry it out,” said Jerry Givens, who was an executioner in Virginia from 1982 to 1999.

“It’s like a scar,” he said. “When you have executions in the future, it will continue to open up that wound and people will have to live with this.”

Bucklew asked the Supreme Court, which already twice has stayed his execution, to let him die by suffocation in a gas chamber instead.

“Participating in executions places a tremendous weight on the shoulders of the execution team,” read the letter from Givens and other former prison system workers.

“When as here, an execution is unlikely to go smoothly, and is likely to result in unnecessary pain and suffering, the burden of participation becomes unbearable.”

Painful memories

Givens carried out 62 executions during his career, using methods of lethal injection and electrocution.

Even when everything went as planned, the 65-year-old told AFP he disliked administrating injections “because I felt too attached.”

“I had my hands on this guy because I was administrating the drug through the syringe,” he said. “So I was pushing it versus hitting a button.”

At the time, Givens said he felt he was simply a cog of justice.

But in the 1990s, he found himself linked to a complex case of stolen cars — and believed he was unjustly condemned.

Givens lost confidence in the justice system and became a fierce opponent of capital punishment.

“The system is corrupt — until you fix it you need to discontinue” executions, he said.

“As long as Americans have executions, the scar for me can be opened anytime.”

‘Post-traumatic stress’

Givens is one of only a few former executioners to talk openly about his experience.

But in recent years, Sarah Turberville, director of the The Constitution Project that is defending Bucklew, said corrections officers have started becoming “vocal about their discomfort in being involved executing prisoners.”

“When a case like Mr Bucklew’s made its way to the Supreme Court, we reached out to them to see if they would be interested in sharing their experience with the high court,” she said.

“As the brief’s signatories illustrate, many were eager about sharing their unique perspective.”

Allen Ault supervised five executions in the 1990s in Georgia.

“Those of us who have participated in executions often suffer something very much like post-traumatic stress,” he told the court. “Many turn to alcohol and drugs.

“For me, those nights that weren’t sleepless were plagued by nightmares.”

But James Willett, who did not sign the letter, said he never lost a wink over supervising nearly a hundred executions in Huntsville, Texas before retiring in 2001.

Willett found that he hardened somewhat over time — but “it never got easy.”

For him, the hardest part was “watching an otherwise healthy person die, especially the younger men, and considering how they ruined what could have been a productive life for themselves.”

© Agence France-Presse