by Martin Parry

Agence France Presse

SYDNEY, Australia (AFP) — Australia must avoid a “dance with dictators” when it hosts ASEAN leaders at a special summit this week, and should make human rights a prominent issue, campaigners say.

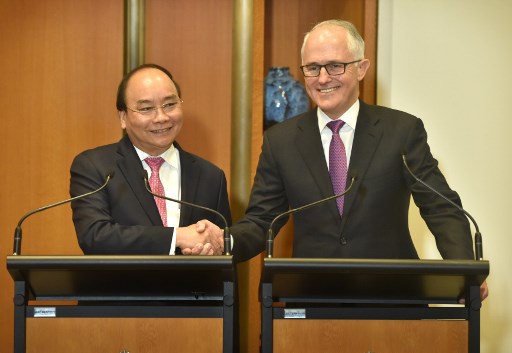

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull will welcome heads of government or state from nine of the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations heads to Sydney from Friday, including Cambodian strongman Hun Sen and Myanmar’s under-fire leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

Australia was among several countries to raise concern about his crackdown at a UN Human Rights Council meeting in Geneva last year.

This weekend’s meeting, initiated by Canberra, is focused on economics and counter-terrorism, but Turnbull has been urged to use the opportunity to publicly raise human rights issues.

“Shutting one’s eyes and hoping that closer trade and security ties will somehow magically transform abusive governments into rights-respecting ones doesn’t work,” said Human Rights Watch Australia director Elaine Pearson.

“The ASEAN summit shouldn’t just be an opportunity to dance with dictators, but a chance to publicly press them over horrific human rights abuses across the region.”

A military crackdown in Myanmar’s Rakhine state that began in August has seen nearly 700,000 of the mainly Muslim Rohingya minority flee to Bangladesh, with pressure mounting on Aung San Suu Kyi after a top UN rights expert warned this week the situation bore “the hallmarks of genocide.”

The Nobel Prize winner is due to stay in Australia for bilateral talks after the summit.

Amnesty International’s director for Southeast Asia and the Pacific James Gomez said Australia and ASEAN leaders needed to take a strong stand against what was happening on their doorstep.

“The human rights crisis in Rakhine State, and Myanmar as a whole must be top of the agenda this weekend in Sydney,” he said.

Tough issues

Hun Sen’s attendance is not guaranteed. He was rankled by reports he could face pressure over his government’s crackdown on democratic institutions and media freedoms, with protests planned by Australia’s sizable population of Cambodian refugees from the Khmer Rouge days.

The notoriously brash Hun Sen threatened to “shame” Canberra and block the release of a joint statement at the summit’s conclusion on Sunday if he was embarrassed.

Australia has been a dialogue partner of ASEAN, which groups Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, since 1974. They began biennial leaders’ summits in 2016, with the first at Vientiane.

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop indicated Canberra intended to tackle the tough issues.

“This is an opportunity for us to discuss issues of concern face-to-face and raise with the ASEAN leaders the value that Australia attaches to protecting and promoting human rights,” she said.

The summit will open with a business meeting in Sydney on Friday, covering energy supply, agribusiness, and tourism, before closed-door counter-terrorism talks on Saturday and then the leaders’ gathering on Sunday.

Canberra has played a key role in helping Southeast Asian states choke terrorist financing and counter violent extremism, with the problem exacerbated by jihadists now being forced out of Syria and Iraq.

The issue was driven home last year when pro-Islamic State militants seized the southern Philippine city of Marawi, with Australia aiding Manila to win it back.

John Blaxland, director of the Australian National University’s Southeast Asia Institute, said he was not expecting dramatic outcomes, but ASEAN leaders meeting in Sydney was itself a “significant inflection point in Australia’s engagement in the region.”

© Agence France-Presse